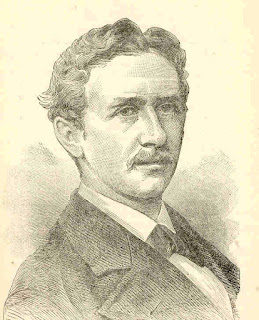

ALEXANDER Mackay liked to tell the truth. Even when it hurt. Or shocked. Or saddened. Just days before he set sail for Uganda in 1876, he made an unusual observation which was to come true.

"I want to remind the committee that within six months, they will probably hear that one of us is dead," he told the committee of the church missionary society at a send-off party for him and eight other missionaries.

Everyone was shocked. People could be seen whispering amongst themselves, according to a report in the CMS Gleaner.

"Yes," he continued. "Is it at all likely that eight Englishmen should start for Central Africa and all will be alive six months after? One of us at least - it may be I - will surely fall before that."

"But," he added, "when that news comes, do not be cast down, but send someone else immediately to take the vacant place."

In less than two years, Mackay wrote home to say that of the eight missionaries, two had died of tropical disease, the natives had murdered two and two had returned to England very sick. Others followed in their footsteps, and some met the same end.

Bishop James Hannington was murdered on his way, as was Bishop Parker. Alexander Mackay outlived them, but only for a little longer.

His story is a fascinating tale of purpose and perseverance amidst persecution. And for this, it has been told and retold by a whole generation of authors in the last century.

In The Story of the Life of Mackay of Uganda, Pioneer Missionary, his sister J. W. Harrison sheds light on his childhood and the events that shaped the man who is sometimes referred to as the modern-day John the Baptist.

Mackay was born on October 13, 1849 in Rhynie Aberdeernshire in Scotland. His father, Alexander Mackay, was a church minister in a remote parish of the eastern highlands in Scotland. Mackay was unusually bright, and by the age of three, could read the New Testament.

Mackay's father was a friend of a number of academics and scientists, one of whom was Sir Roderick Murchison, David Livingstone's sponsor and after whom the Murchison Falls is named. At 14, as he was about to join grammar school, Mackay lost his mother and he was never the same again.

His sorrow and loneliness kindled a thirst for adventure in him and a deep fascination with machines. It is said that he would often walk for miles just to see a railway engine.

His parents had hoped he would follow in his father's footsteps and become a church minister, but while at Edinburgh University, Mackay begun to concentrate on engineering and soon, he was studying higher mathematics and surveying.

In 1873, he went to Germany to study German. While here, he got a job as a draughtsman at the Berlin Locomotive Works and invented an agricultural machine, which won first prize at an exhibition of steam engines in Breslau.

At the teacher training college in Edinburgh, he had had a reputation as a loner and he did no better in Berlin although he wrote frequently to his family.

"Here I am," he once wrote, "among all these heathen people; almost all are infidels, but agree in so far acknowledging the existence of God as to continually use the expression `Ach Gott (Oh God)' often more than once in the same sentence.

On this account, I am obliged to have as little conversation with them as possible and hence cannot have the advantage of German conversation as I would like."

During his stay in Berlin, Mackay resided with the family of Hofprediger Baur, one of the ministers of the cathedral there. Under Baur's influence the fascination of missionary life, which he had felt in his youth, was revived in him and he begun to study the Bible.

It is while he was in Germany that his sister wrote to him, and told him about a missionary expedition to Madagascar, which Mackay decided to join as an "engineering missionary". His vision was to connect Christianity with modern civilisation and he hoped to do so by establishing a college to train young men in religion and science.

He also wanted to build railways and roads, which he described as "an enormous enterprise for one single-handed".

Months before he was due to set off for Madagascar, the mission fell through, and he was asked instead to go to Mombasa to oversee the settlement of liberated slaves.

This journey too, hit a dead end, and someone else got the job before Mackay's formal application went in. It was around this time that the London Daily Telegraph published a letter from the explorer Henry Morton Stanley asking for missionaries to be sent to Uganda.

Mackay applied to the CMS to be part of the Uganda mission, also known as the mission to Nyanza, and on April 27, 1876, set sail on the steamship, the SS Peshawar, from Southampton.

Arriving at Zanzibar on May 30, 1876, Mackay and about eight of his colleagues set off for the interior. It took him well over two years to travel from the coast to Buganda. One after another, his colleagues died along the way until he was the only one left.

All through his travels, he kept a journal (currently kept at the CMS archive library in London) in which he jotted his impression of the people and the culture and lifestyle of the various African tribes he visited on his journey.

In one of his entries he observes: "Go where you will, you will find every week and, where grain is plentiful every night, every man, woman and child, even to suckling infants, are reeling with the effects of alcohol."

Because of this, he writes, he became a teetotaller from the moment he left the coast.

In November 1878, Mackay arrived in Buganda and established his headquarters at Nateete, where he set up his printing and engineering workshop. In time he built a medium-sized storeyed bungalow.

His was the first house ever in Uganda to be built with bricks. The house's foundation was made of burnt bricks while the walls were built with sun-dried bricks.

In March 1882, Mackay baptised his first five converts among them Sembera, and three of the king's pages, named Mukasa, Kakumba Lugalama. Others soon followed.

It is said Mackay would print large letters on sheets of paper, which he used to teach his young converts to read and write Swahili. He also translated the gospel of Matthew into Luganda.

His first printing press, a small hand-operated machine, is on display at the Uganda Museum, while a church and school (Mackay College) now occupy the place where his workshop once stood.

Mackay was not only keen on winning more souls for God, he also put in long hours teaching his new converts new skills such as building roads, houses, machinery, and boats as well as reading and writing.

It is evident from Mackay's journal that he was a good friend of Kabaka Muteesa's and the two would talk often. In one of his entries, he recounts that the Kabaka once asked him to help him obtain an English princess, so that he could add her to his numerous collection of wives and was astonished when Mackay told him that in England "no woman could be given in marriage without her consent".

Another time, Muteesa said: "Mackay, when I become friends with England, God in heaven will be the witness. God will be the witness that England will not come to make war on Buganda, nor Buganda go to make war on England.

Everyone will say: `Oh Muteesa is coming,' when I reach England, and when I return: `Oh Muteesa is coming back again.'"

Although the Kabaka never did make the royal journey, three of his emissaries eventually did, one of them Ham Mukasa Mulira.

But despite their friendship, Mackay despised the "heathen" practices of the king which prevented him from being baptised. He writes how the unfortunate victims of Muteesa's displeasure would be slowly tortured to death, their noses, ears and lips cut off.

For others, he says, the sinews of their arms and thighs would be cut out and roasted in front of their eyes, before these were put out and the body itself burnt alive.

"The wretch who orders all this to be done for his own gratification is he who is called in Europe `the enlightened and intelligent king of Buganda'".

He also writes about some of the barbaric practices of the king such as the kiwendo (a great human sacrifice to secure blessings from a departed king). For instance his journal entry of February 6, 1881 reads thus: "Two years ago the king gave orders for a kiwendo and 2,000 innocent people were slaughtered in one day.

Less than a year ago a similar atrocity was committed. Two thousand poor peasants were caught, fastened in forked sticks, kept in pens and murdered on the set day, as an expiatory offering to the departed spirit of the former king, Suna.

Now another kiwendo is about to take place, because the king is ill and a sorcerer has told him that only a great slaughter can heal his sickness." Risking his life, Mackay wrote the king a letter, pleading for their lives, but his plea was disregarded.

Muteesa, for political reasons, played off Catholics, Protestants and Muslims against each other, and played all three new religions off against the traditional priests, working them all to his own advantage.

Mackay and the White Fathers played directly into Muteesa's hands, spending more time maligning one another than they did working together.

Life, however, became increasingly difficult for Mackay after Muteesa's death. He writes that the new Kabaka, Mwanga II, had a cruel streak and was easily influenced by his chiefs. "Our young king has some good points, but I fear few.

He is much afraid of his older chiefs when it is a question of doing anything in what we would call a right direction. No such scruples seem to come in way when he wants to kill a score of two of his subjects."

The new king was also under the influence of Arabs at court and he had become addicted to smoking bhang like them. Much worse, he had acquired a taste for sodomy.

Indeed, Mackay writes that the martyrdom of Christians in Buganda was sparked off by a related incident after one of the pages, Apollo Kaggwa, refused to service the king. In his journal, he describes the incident as "an act of splendid disobedience and brave resistance to this Negro Nero's orders to a page of his, who absolutely refused to be made the victim of an unmentionable abomination".

Mackay says that the king went berserk and summoned every page at court. He then asked those assembled which of them was a Christian. Thirty stepped forward and thus began the Christian martyrdom.

And when his palace burned down one day, all blame was laid squarely on the Christians (the thatched roof had accidentally caught fire when one of the pages was out praying). Three Christian boys - Seruwanga, Yusufu, and Lugalama - were arrested, tortured and burned on a slow fire for their negligence. Another Protestant page was speared to death.

Then three Catholic pages were beheaded. The next day, two more Protestant lads were castrated and died, while a couple of Catholics were hacked to pieces. Others were picked off in ones and twos.

For a few months, there was a halt to this carnage. Then in 1886, 26 of the pages - 13 Catholics and 13 Protestants - were marched 16km from the capital and burned alive in a huge bonfire at Namugongo.

In all, about 200 Christians were tortured and burned. Their death and Mwanga's continued persecution of Christians weighed on Mackay's conscience as he could only watch helplessly as his former pupils and friends were murdered.

In 1888, it seemed the persecution would stop when Mwanga was driven from his throne by the Muslims and replaced by his elder brother Kiweewa, during the inter-religious wars. Mackay held on, despite the bloodshed and the civil war, and was always hopeful of establishing a permanent station.

Months later, Mwanga was re-installed by the Christians after defeating the Muslims, his suspicion and growing dislike of Mackay continued and he decided to leave.

Twice, Mackay and Ashe tried to leave, but they would always be intercepted and marched back to Nateete by the king's chief warrior. A year later, on July 21, 1887, Mackay was allowed to leave Buganda and he travelled to Usambiro on the southern shores of Lake Victoria, where he stayed for the remaining three years of his life.

A great deal of his time was spent urging the British government through the consul at Zanzibar to annex more territories in Africa to prevent "dictatorial rulers" such as Mwanga from "inflicting atrocities on their own people."

Mackay was also shocked at the apparent indifference of Christians in Europe to the martyrdom of black Christians in Africa when at the same time, they could be roused to a fury at the murder of a white Christian bishop like James Hannington.

On February 14, 1890 Mackay caught malarial and four days later he died at Usambiro, the last survivor of the little band of eight that had set out for Uganda in 1876.

He was buried at Usambiro and his remains were later transferred and buried at Namirembe Cathedral.

Originally published in the Sunday Vision in 2006.

This is one of the stories I enjoyed researching and writing while at the Sunday Vision. It was a joy discovering some really amazing old books at the Uganda Society Library at the Museum, and the Africana Section at the MUK main lib. I set out to write one story - on Damalie Kisosonkole, the late Nnabagereka/stepmom/maternal aunt to the Kabaka but ended up writing three instead, including one on the historical figures buried in Namirembe cathedral's graveyard; and this one on Alexander Mackay, whose wry sense of humour and passion for social justice strangely resonated with my own.

ReplyDelete